Published by Bob Elliott on Aug 22, 2022 2:52:00 PM

All eyes are on Chairman Powell’s speech this week for his thoughts on how he will tackle today’s inflation challenge. This inflationary cycle is new to many investors, but it’s a challenge the Fed has faced before. The lessons learned from those experiences are the best guide to the Fed’s actions in the future. Today’s investors might be better off looking at Paul Volcker’s experience decades ago than trying to read the tea leaves of Powell’s speech today.

Volcker is remembered today as having the courage to run tight enough policy to break the back of inflation. That is a far too simple view. Below we draw insights from a series of lectures Volcker gave years later which give a visceral sense of the challenges he faced and the lessons learned. It took 3 years. Multiple times he thought he had succeeded and eased policy only to reignite inflationary pressures. He was criticized for being both too tight and too easy. It was never really clear what drove inflation, and only tighter money seemed to contain it. While in the end he was successful, it was an extremely difficult and volatile path.

Source: FRED

Most investors today are poorly positioned to go through a similar experience. They are structurally positioned to benefit from strong growth, low inflation, and easy money. The last decade only reinforced this bias and today’s markets are pricing a quick return to normalcy. We’ve highlighted in recent weeks how Hedge Fund managers are better positioned to withstand an inflationary cycle and tightening in response (here), reflecting the lessons learned from these previous inflationary cycles in their portfolios. We hope other investors benefit from these lessons and insights into others’ views to more effectively position for something few of them have ever seen.

Volcker’s Inflation Fight In His Own Words

Roughly a decade after the inflation fight Powell’s series of lectures at the Woodrow Wilson School codified into the book Changing Fortunes give unique insight into Volcker’s experience in the postwar era. It is a fascinating history of the post-war economy, markets, and policy told by Volcker who was in the center of it all.

One chapter covers Volcker’s experience in his first few years as Fed Chairman fighting inflation. While it’s worth reading the whole thing if you can get your hands on it, the quotes below provide the highlights of Volcker’s visceral experience through the inflation fight. Many things read as if they came from today’s papers.

When Volcker was selected to become Fed chair in the summer of 1979, the Fed was facing significant difficult in establishing credibility to fight inflation:

“The intensity of inflation of course had something to do with the intensity of the two oil crises. But it also was certainly connected with a feeling that things were out of control […]”

“In market talk we always seemed to be ‘behind the curve’ reacting too slowly and too mildly only after the evidence was abundantly clear, which by definition was too late.”

Volcker recognized that because other forms of policy were so politically charged, it really was only monetary policy that could solve the inflationary problem:

“Now one can argue about just why all the problems had piled up, but one thing was clear to me at the time. If all the difficulties growing out of inflation were going to be dealt with at all, it would have to be through monetary policy. It was not just that other policies seemed to be caught in a sort of political paralysis, but that no other approach could be successful without a convincing demonstration that monetary restraint would be maintained.”

Delivering tight enough monetary policy was very difficult because there was significant pressure on the Fed to ease in order to be responsive to slowing growth and the possibility of recession.

“The immediate situation was complicated by considerable concern, shared by the Fed staff, that a recession was imminent and perhaps had even begun… Those concerns had naturally led to a certain hesitation about tightening money very much […].”

“But it is also a great psychological fact of life that the risks almost always seem greater in raising interest rates than in lowering them. After all, no one likes to risk recession, and that is when the political flak normally hits.”

“Certainly we had to be conscious of the warnings of recession. But I, at least, was convinced that possibility could not be allowed to dominate our decision making.”

Not everyone on the Fed board was convinced that dramatically tighter monetary policy was needed. Just a month after Volcker began, in September 1979 the board had a 4-3 split vote to increase the rate 50bps which was made public.

“To [the media], the split vote spelled hesitation and left the impression that this could be the Board’s last move to tighten money. The whole maneuver was therefore counterproductive in seeming to send a message that inflation could not be, or would not be, dealt with very strongly.”

That didn’t dissuade him from further tightening, after announcing a major shift to significantly tighter policy in early October 1979 including hundreds of basis points rise in short and long rates:

“We soon learned that any dreams we might have had of changing public expectations by the force of our own convictions were just that – dreams.”

It didn’t work and inflationary pressures continued to build. By early 1980, Volcker needed to do more and implemented a series of coordinated policies that brought the Fed Funds rate to 20%, a massive tightening.

“After all the trouble we had had trying to stop the money supply from increasing, it suddenly dropped precipitously. We could only catch up with that, like the decline in the economy itself, when we got the statistics a few weeks later. As soon as the magnitude of the drop became apparent, money was eased. But there was a lot of criticism from economists, monetarists, and Keynesians alike that we hadn’t moved fast enough; we were willing to put the country through the agony of high interest rates when inflation was raging, but we weren’t doing enough to prevent a crash.”

The significant easing by July caused a large rebound in economic conditions. The ‘recession’ was really only 4 months:

“The net result might not have been much of a recession, but there wasn’t much progress on inflation either. It kept running at double digits and with the money supply rising strongly again we were in the position of tightening money and raising the discount rate a few weeks before the election. It was small comfort that Ronald Regan, as a candidate, criticized the Federal Reserve for being too easy!”

An important part of the dynamic was the incredible uncertainty about what was needed to be done to contain inflation. Even with all the resources available to the Fed, no one really understood exactly what was necessary to achieve success fighting inflation.

“With the best staff in the world and all the computing power we could give them, there could never be any certainty about just the right level of federal funds rate to keep money supply on the right path and to regulate economic activity. The art of central banking lies in large part in approaching the right answer from a sense of experience and successive approximation.”

By mid 1981 inflation once again accelerated and Volcker faced the difficult decision of whether to continue further tightening in order to break the back of inflation at the cost of creating a meaningful recession. Up until that point, unemployment had only gone up a little over 1% and demand and production had been reasonably strong. Years later he walked through what he thought about to get comfort to pursue extremely tight policy that eventually worked in structurally slowing inflation:

“The fact is that from my own admittedly partial and prejudiced perspective, there was substantial support in the country for a tough stand against inflation, for all the real pain and personal dislocation that seemed to imply.”

“In the end there is only one excuse for pursuing such strongly restrictive monetary policies. That is the simple conviction that over time the economy will work better, more efficiently, and more fairly with better prospects and more saving in an environment of reasonable price stability. […] I defined ‘reasonable price stability’ as a situation in which ordinary people do not feel they have to take expectations of price increases into account in making their investment plans or running their lives.”

“The trouble is that when everyone expects inflation, and interest rates go up in anticipation, the temptation always remains to speed up the inflation a little more if not deliberately then for the fear that restraint will cause a recession. In the end there will all too likely be a still bigger recession, and more agony in restoring stability.”

“It may be hard to prove this point with rigorous mathematical reasoning and statistical techniques used by modern economists. But there are real doubts that those techniques can ever capture all the complexities of human behavior. By and large, the world’s governments … seem now to have come to the conclusion that price stability is a prime priority, and obtaining it is worth a lot of transitional agony.”

Volcker summarizes the experience managing monetary policy by recognizing the imperfections of managing policy through the period. He suggests that despite the challenges what needed to remain paramount was running policy tight enough to break inflation. He succeeded through trial and error, but after three years eventually accomplished his goal.

“We are all perfectionists. Looking back there is a certain amount of second guessing, including by many experts sympathetic to the dilemmas faced by the Federal Reserve, about whether we weren’t too slow to ease in 1982. Maybe, they say, the recession could have been ended a few months earlier. Perhaps this is true, but those arguments do not impress me much. It’s not that our policies were perfect, but that the far greater error at that point would have been to fail to follow through long enough to affect fundamental attributes and really put inflationary expectations to rest. Those policies cannot really be finetuned […]”

Volcker’s Inflation Fight In Charts

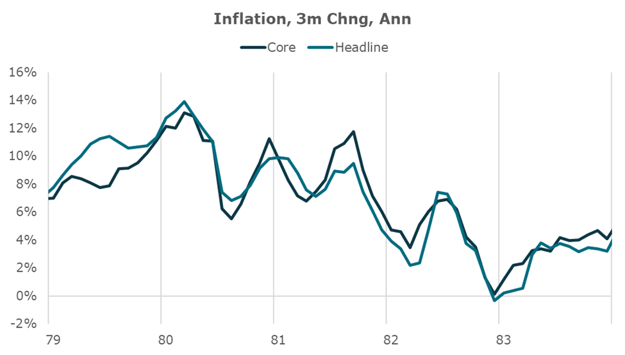

In addition to the words from above, the charts below provide context on the macroeconomic and market conditions through the Volcker tightening period. It was a time of exceptional volatility in the economy and asset markets. Across the period of 3 years there were several smaller cycles of tightening, slowing, easing and reacceleration. The traditional 60/40 portfolio did poorly through most of the period. Commodities, gold, and the dollar outperformed at various points. It was only after prolonged tightening and significant recession that inflationary pressures eventually eased.

Rather than comment on each individually, they are presented below as an appendix to be iteratively explored along with the policy chart above. The date lines should be used to think about the leading and lagging effects of policy actions. All the data presented is sourced from the FRED database where you can find countless more series during that time to inform your thinking. Just in the way the words above give a visceral sense of Volcker’s experience so too can these charts allow investors today to relive the experience.

For informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. The historical analysis discussed herein has been selected solely to provide information on the development of the research and investment process and style of Unlimited. The historical analysis should not be construed as an indicator of the future performance of any investment vehicle that Unlimited manages. No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee return or eliminate risk in any market environment. No Representation is being made that any investment will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown herein.